Not So public, public spaces.

Sanayeh Garden from behind a dust filled window, Beirut, Lebanon – 18 May 2022, Photograph by Chloe Khoury

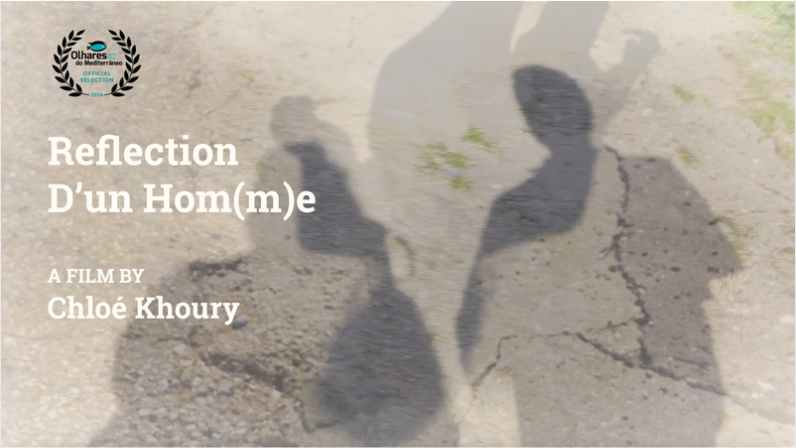

On a sunny afternoon in Beirut, Talal and Afif, retired dentists and life-long friends are taking a stroll with Talal’s wife in the Sanayeh Public Garden, one of Beirut’s only green public spaces.

As they walk, they reminisce about what Beirut used to be, the public space, the people, the coffee and the flowers. We, Lebanese, have heard those stories before, from our parents and grandparents whose eyes light up as they recall shared time and space. Stories about a time before Downtown Beirut was largely privatized and the city gave up its green spaces to the footprint of modern structures. Before the coastline, unwillingly, withdrew its sand and sea from the people, unless they paid to enter the new beach resorts.

“We always walk together,” said Talal. “We call each other on the cellular and meet here three to four times a week.” For a brief moment he lets go of his wife’s hand to raise his own to his ear, feigning a phone call.

Social connections in Lebanon have always been crucial, yet gathering places, whether they are houses, restaurants, malls or beach clubs, are private. Beirut has only 0.8 square meters of green space per capita while the World Health Organization recommends 9 square meters.

Our country’s less privileged children play in the streets, the only public space they have.

In between cars that rarely respect the speed limit, they run after the balls and chase each other up and down the road, their feet stomping on the asphalt, creating echoes that penetrate our houses through our open windows.

“We come here because there is no other public space for us to go near our houses,” said Afif.

Density of buildings, Beirut, Lebanon – 18 May 2022, Photograph by Chloe Khoury

Ideally they would have gone to the corniche today. They had to reconsider their choice, not because of the brownish layer of pollution floating over the sea – they got used to ignoring it and looking away. They had to reconsider because it is not within walking distance and, as their incomes collapse alongside Lebanon’s economy, they can no longer afford the fuel to drive there.

“There is no municipality nor government we can count on to enhance our lives. Five years ago, the Beirut municipality started a public garden project; to this day, they have only managed to put the sign up,” Afif laughed.

“At least we have the Sanayeh Garden, that is clean, where we can get our daily dose of sun and fresh air,” Talal tried to convince his friend.

But, Sanayeh, although a green space, is not a public space. Even though it is free to enter, it remains a privatised park which is often closed, even during opening hours, and highly regulated. People are not allowed to sit on the grass, bring in a camera, nor play with a ball.

Talal studied in Ukraine where he met his Ukrainian wife. During our conversation, he mentioned that international organizations and the civil society were spending too many resources supporting “immigrants” rather than Lebanese, unaware of the contradiction between his words and the presence of his immigrant wife beside him.

In another part of the park, 38-year-old mother of two, Lama, watched over her daughter.. Sanayaeh, she explained, is conveniently close to her son’s day-care, and going there allows her children to meet and play with other children from different ethnicities and backgrounds. Many of her friends, she said, would not come at all, let alone with their children, because they do not want to mix with Syrians and Palestinians. “They would rather pay to use a private place,” she says. But I don’t mind.”

Lebanon’s past conflicts have altered people’s relation with public spaces. The civil war divided the capital between east and west, drastically reducing Beirut’s historical public spaces and contributing to social segregation and sociocultural distortion. Those spaces should not be a reserve for the country’s elite.

Instead, they need to be understood as a breath of fresh air, a place where people can let their imagination and creativity run free between the colours and perfumes of the flowers and the birds chirping on the trees.

Developing public spaces requires a shared vision. Those implementing them need to understand how those spaces can equally benefit them.

Municipalities which lack financial and technical resources for urban planning need to come together with citizens, architects, urban planners and local civil society organizations to design public urban spaces that can be used by people to nurture a common feeling of belonging and reclaim their right to smile and feel at peace.

“In Hasbaya, the village I come from in the South, the municipality created a clean, green public garden. The municipality in Beirut could replicate those projects here and make them even nicer, but they don’t. Once the fuel crisis is resolved, I will go there, to walk in nature, look at the colours and smell the perfume of the flowers,” said Talal.